Correlation or Causation? New Studies Reconsider Music and Brain Function

by Carolyn Heneghan

Does listening to music enhance test-taking abilities? Does music exposure from a young age guarantee a better memory in the future?

These are questions that surround the concept of music and the brain, and many research teams have tackled the subject over the years. New findings at the Boston Children’s Hospital may shed some light on this concept.

Researchers led by Nadine Gaab, Ph.D of the Laboratories of Cognitive Neuroscience at Boston Children’s, have recently released a study that may have some influence over the opinion as to whether or not music training has anything to do with enhanced brain function.

While there are many notions regarding the relationship between music and brain function, it is important to consider all aspects of these studies before reaching a conclusion about whether or not listening to or learning music actually causes cognitive improvements. A simple correlation is always possible.

The Harvard Study

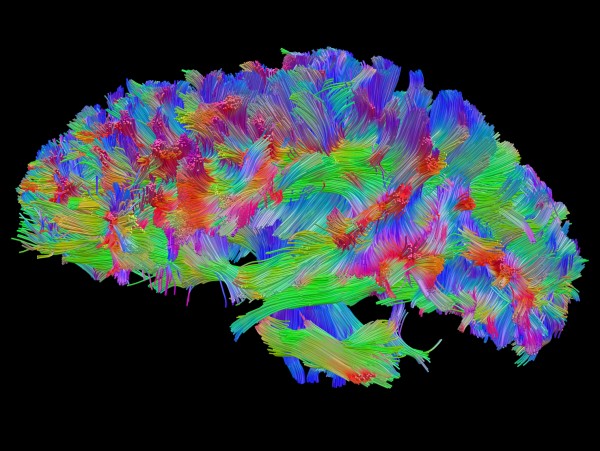

In this experiment, researchers had two separate groups of test subjects: 30 adults, half of whom were working musicians, half of whom were not, and 27 children aged 9-12, 15 of whom had at least two years of musical training. While under the careful watch of an MRI, test subjects were asked to perform certain cognitive tasks to measure various aspects of cognitive ability. These included mental processing speed, verbal fluency and working memory—your mind’s ability to hold multiple ideas at the same time.

According to the study, researchers concluded, “Children and adults with extensive musical training show enhanced performance on a number of executive-function constructs compared to non-musicians, especially for cognitive flexibility, working memory and processing speed.”

But what does this mean for music’s causation of improved brain function? Has past research supported these findings, and does this new research build upon it?

Past Research and Results

Leading up to this study, other research pointed to a number of different reasons why or why not music may be responsible for promoting brain function. For example, a 2013 study in Canada led by Harvard researcher Leonid Perlovsky found that, among high-performing high school students, those who continued music classes had consistently higher grades than those who dropped music lessons after two years of compulsory training.

In a previous study by this group, researchers were able to demonstrate that when subjects listened to pleasant music while taking an academic test, those subjects were able to overcome stress, devote more time to more stressful and more complicated tasks, and their grades were higher.

These are just a couple of the many studies done over the years that have worked to either prove or disprove the idea that music causes improvements in brain function.

Correlation or Causation?

With all of this research done, have researchers been able to prove that learning music can improve intelligence and higher brain functions?

Unfortunately, this research still does not conclusively prove causation between music lessons and mental abilities. Rather, the studies prove correlation between music abilities and higher brain function, but they cannot discern which came first.

Was the higher brain function caused by the music studies? Or were those individuals able to excel in music because of their innate higher brain functions? Did music allow students to perform better on a test? Or would the students have performed better anyway because they were already more gifted and motivated?

This classic chicken-and-egg predicament continues to plague researchers who aim to prove a commonly held belief—that music does indeed boost intelligence and improve brain functionality.

While many schools are dropping their music and other arts programs in favor of more math, language or test preparation, many researchers, teachers, musicians and other music lesson supporters are campaigning for the importance of music and arts to a prosperous and well-rounded education. While these schools believe that they are benefitting students by allowing for more test subject-specific class hours, music class supporters believe that they may be doing more harm than good in terms of other cognitive areas.

With all of this in mind, Perlovsky and his colleagues still hold the belief that the value of music, from an evolutionary perspective, involves its ability to help people cope with cognitive dissonance—in other words, the feelings of discomfort that accompany an encounter with information that contradicts a core belief.

Some researchers say that music has become ubiquitous because of its benefit to early humans as a way to cement social bonds, which ultimately contributed to further evolution and eventually improved civilization.

Whether or not music conclusively contributes to higher brain function is still up for debate and will be left to more studies in the future, particularly those who can follow test subjects from before, during and/or after their music studies and test their brain functions at those different times.

One aspect that cannot be argued is that music plays a crucial role in society—past, present and future. For this reason, more studies will inevitably be done until the spellbinding question can be answered: Does music really make us smarter?